Waste Colonialism

The hidden costs of fashion’s waste crisis.

The fashion and textile industry faces a significant waste crisis, driven by overproduction and overconsumption. Each year, millions of tonnes of clothing are discarded, an overwhelming portion of which is exported to countries in the Global South, causing environmental and social harm. As a textile-recycling service with a mission of addressing this issue, we see the hidden problems and the urgent need for change.

With the rapid rise of fast fashion, we have adopted a throwaway culture and an out-of-sight out-of-mind mentality that sees the UK sending 300’000 tonnes of clothing to landfill each year - a high portion of which is still wearable. As a society, we have an inherently detached relationship with our clothing, leading to the rapid consumption and disposal of low-quality garments that far exceeds the capacity of charity shops, take-back schemes and textile reclamation sites. In the UK alone, approximately 650'000 tonnes of unwanted clothing are collected from charity donations, clothes banks, take-back schemes and textile recycling banks each year. Garments, regardless of their condition or material, are donated without a second thought and most of these donations cannot be resold or recirculated. According to Aja Barber, in her book Consumed, about 10-20% of donated clothing gets resold. As a result, post-consumer clothing donations and post-industrial textile waste are increasingly exported to countries in the Global South. Despite the industry's best efforts at implementing circularity initiatives and employing sustainability jargon, there still seems to be an overwhelming masking of the waste crisis and the reality of the sheer volumes of waste that the fashion and textile industry generates. The industry is at a tipping point, and we cannot carry on with business-as-usual.

Secondhand clothing is often perceived as beneficial and positively sustainable, as it enables consumers in the Global North to perform the philanthropic act of donating to charity, with the assumption that this is beneficial for all involved in the secondhand value chain. Yet the reality of this is that communities in the Global South are burdened with the stifling role of managing the excessive volumes of waste of the Global North, tackling a problem that they played no part in generating. This is destroying the local textile and craft industry, causing environmental degradation, and placing communities in severe debt cycles as they are forced to pay the cost to mitigate the waste. This is waste colonialism, defined as the domination of one group of people in their homeland by another group of people through waste and pollution. As it currently operates, the secondhand clothing trade exists to enable the linear fashion system to continue with ‘business as usual’, perpetuating ideologies of waste colonialism.

Take Kantamanto market in Ghana, for example, the largest secondhand clothing market in the world - flooded with approximately 15 million garments every week, that market retailers purchase in large-scale clothing bales to resell. Kantamanto has no agency in deciding what will influx the market each week, meaning the Global North controls the narrative, deciding what is ‘waste’ and what is not. This often results in low-quality clothing arriving in unsellable conditions; according to some estimates, only 18% of the average clothing bale is of adequate quality to be resold. This means many retailers are left with low-quality clothes they are unable to sell, leaving them in vicious cycles of debt while the textiles are sent to landfill, or found clogging gutters or as tangled masses washed ashore on Accra’s beaches.

The secondhand clothing trade circulating Kantamanto was first described as ‘Obroni W’awu - meaning Dead White Man’s Clothes. This name alludes to the sheer volume of secondhand clothing that began arriving in Ghana in the 1950s, during the colonial period, stemming from the idea that someone must have died to give away such ‘nice’ items of clothing. Here, nice refers to Western, as during the colonial rule, citizens had to conform to the professional dress codes that were defined by the British. Therefore, Western clothing became considered desirable as it signified status, power and wealth and this is where the demand emerged. This demonstrates how the secondhand clothing trade emerged in Ghana and conveys a sense of where the influx of secondhand clothing began decimating the local textile industry. From 1960 onwards it became increasingly difficult for the local textile economy to compete with the influx of cheap secondhand clothing and this is still visible today.

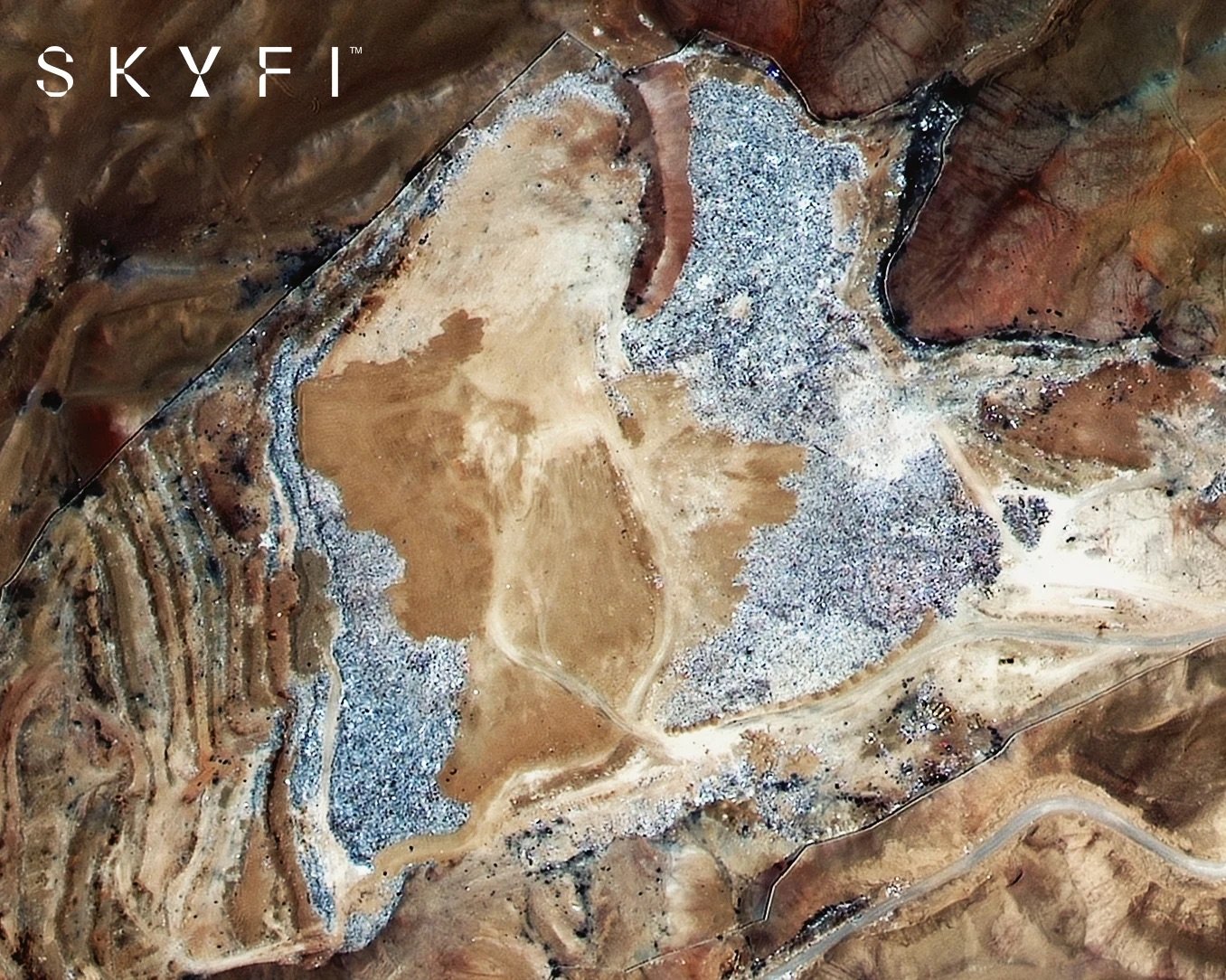

Another country bearing the burden is Chile, where 60’000 tonnes of used clothing are exported each year to the Atacama Desert, making the beautiful and desirable desert landscape now one of the world’s fastest growing dumps of discarded clothes. This contributes to the degradation and pollution of the natural environment as the landscape is overwhelmed by synthetic materials that cannot biodegrade. With the clothing landfill now visible from space, the Global North’s waste is made starkly visible and it cannot be ignored.

Here, textile waste pollutes the environment, fuels fires, immensely contributes to fashion’s carbon footprint, and destroys local livelihoods. As a result, the local community faces stigmatisation for the dumpsite and lives in a heavily polluted environment. Meanwhile, the brands and businesses in the Global North, responsible for generating and exporting the waste, carry on unscathed, continuing to ship western cast-offs to countries in the Global South to bear the burden, evading responsibility for their waste.

Waste colonialism in the fashion and textile industry needs urgent addressing. This harmful narrative that treats the disposal of poor-quality clothing as the norm needs to be challenged, as communities in the Global South are paying the price. We need to rethink our damaged relationship with clothing and move away from the throwaway culture that drives overproduction and overconsumption. We must challenge the industry to take accountability and be more radical in our approach to drive change. As citizens we need to acknowledge our role in this system and recognise that donating clothes to charity does not have a positive impact if the clothes being donated are in poor condition - which includes, dirty, stained, broken and in need of repairs. As Aja Barber says, we should only donate clothing that can be reworn; ask yourself if you would wear it in its current condition, if the answer is no, it should not be donated. Clothing that is low-quality, stained, damaged and falling apart must be recycled responsibly, for example, by shredding the waste material into new recycled fibres that can be made into new materials. Which is our solution-driven approach at FibreLab, aiming to re-use, repurpose and recycle the Global North’s waste hyper-locally, within the UK.

Resources to learn more about waste colonialism:

Books:

Consumed by Aja Barber

Clothing Poverty: The Hidden World of Fast Fashion and Second-Hand Clothes by Andrew Brooks

Organisations:

The OR Foundation https://theor.org/

Fashion Revolution

Remake

Podcasts:

The Wardrobe Crisis Ep 15-, Liz Ricketts - Waste Colonialism and Dead White Man’s Clothes

Conscious Style Podcast - Fashion’s Waste Crisis in the Atacama Desert